In Part 1 of this mini series on Runner’s Knee, you discovered that all is not quite how it seems when it comes to knee pain – or any other long term pain for that matter. You discovered that pain and injury are two separate things and don’t necessarily show up together. This can make it really hard to get to the source of longer term pain than presents as a running related injury. In this article I want to give you some real reasons why you may still be getting knee pain weeks, months or even years after the original trauma.

I’ll present one case study here, and follow up with more over the coming weeks.

Firstly though, for the avoidance of doubt, tissue issues are real things. Strains, sprains, tears, breaks – they are very real and just because they may not always be associated with pain (but in most cases they are for the reasons mentioned in Part 1), if you are in any doubt whether you have a physical injury or not, then you need to get seen by a medically trained professional – ideally someone who has experience of dealing with active people and specifically runners.

OK, now we have established that, let’s start looking at some case studies where runners have come to me with painful knees, hamstrings, ankles, IT Band etc. In many cases they have had this pain for months and months, and a few of them have had the pain for years and have seen a wide variety of very well meaning professionals that have helped somewhat but not quite got to the source of the issue. I want to give you a high-level overview of how they presented, some of the things I tried; what didn’t work and then what did work (with varying degrees of success).

Runner 1: Outside of right knee very painful for the last three years.

Introduction

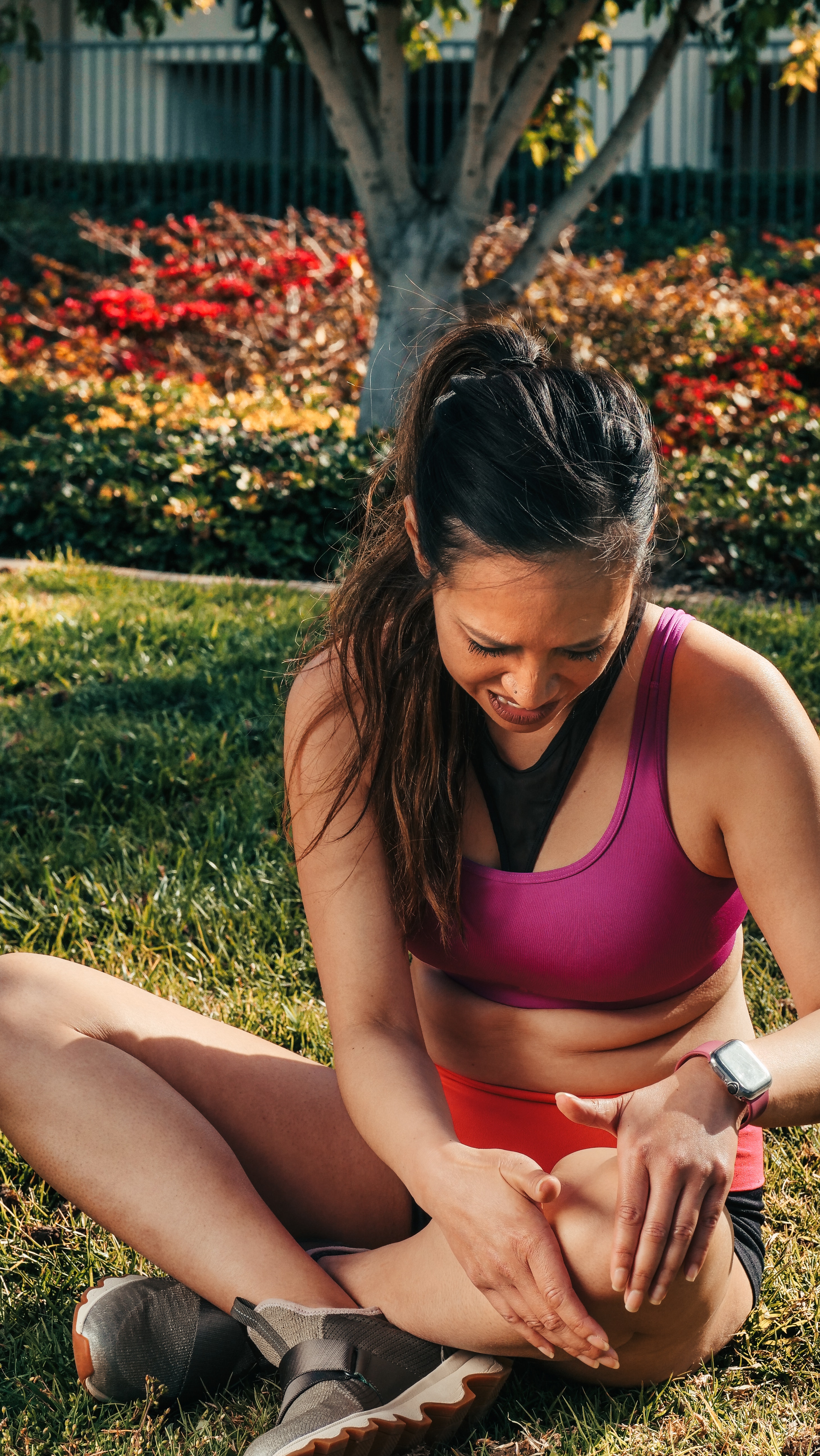

Runner 1, we’ll call him Jim as that’s not his name, came to me for a running assessment as he had been getting pain in the outside of his right knee for the past three years. The only way he could run without pain was with a knee brace. He had a number of different types of knee brace from simple thin neoprene ones to more sturdy neoprene ones with built in hinges. This last type was the one he used most often as it gave the best relief, although it was quite cumbersome and very hot to wear.

Over the previous three years he had seen different practitioners, and at one point saw a physio once per week for three months. Unfortunately, nothing worked and the end result was always the same – he had to go back to running with a knee brace.

He eventually came to me on a recommendation. Jim’s thoughts were that something about his biomechanics (running technique) was leading to the knee pain and if he could improve his technique the pain would go away. Jim was also very concerned that if he ran with the knee pain (i.e. without the brace), he would be doing himself damage and severely injure the tissues.

The assessment

I always start my assessments with some basic pain and neuro education. After listening to Jim’s background and discussing his pre-submitted health forms, I explained how pain and movement works through an applied neurology lens. I often begin this education piece with the information in Post 1 of this mini series and expand from there as necessary. I find this helps to relieve some of the fear that you may have over damaging tissue when you run in pain. Let’s be clear though, running through pain is never a good idea, but the reframing of pain Vs injury helps you to take a step back and look at your situation more objectively.

Following this discussion, I stuck a load of dots on Jim and observed him walking up and down my office; taking video for discussion later in the assessment. How you walk gives me a wealth of information about how well your brain and nervous system is integrating with your muscles, and how well you unconsciously control certain movements. Jim then walked on the treadmill as it gives me slightly different data, and then he did a very small amount of running (both barefoot and in shoes) so I could capture the most important movement patterns as he ran. Now onto the really fun bit.

The rest of the assessment was made up of lots of brain-based tests and drills designed to look at Jim’s movement patterns specific to running. So in this section, I’m looking for things like coordination, agility, stability (both conscious and reflexive), balance, and your ability to express and control strength in certain movements. In Jim’s case, I also wanted to look at his sensory system in depth. From Jim’s pre-submitted forms, I had designed some tests to specifically assess how his sensory input may be contributing and impacting his knee pain.

Sensory Mapping

You may not be able to fully appreciate why this is important, so let’s take a very brief detour into the world of sensory mapping…

Without wanting to go into any complicated explanations, science has revealed to us that you have a number of virtual maps of your body that sit in various areas of your brain. These maps detail parts of your body with particular reference to controlling movement. The only way these maps can be kept to date is through the sensory input that comes in from those areas. If the maps go out of date or get blurry, your brain cannot accurately identify where that body part is so cannot move and control it well.

If the brain doesn’t feel ‘safe’ in knowing where a body part is, you won’t be able to be strong in that area and you may well be inaccurate when trying to move. Let’s just say that the body part in question is your knee. If this map is blurry, then your brain cannot identify where your knee is, so it can’t move it well. In addition, this inability to move well spills over into not being able to stabilise your knee joint.

As I’m sure you can imagine, when you are running your ability to stabilise your knees is very important. If you aren’t able to do this, your brain doesn’t feel ‘safe’ and predicts that this could lead to a physical injury. In order to get you to do something about it (initially, to stop this threatening activity of running), it gives you the experience of pain. But get this, it may not be the map of your knee that’s blurry. It could be your ankle or your hip and your brain is using pain in the knee because it knows you’ll pay attention to it.

Updating Jim’s Brain Based GPS

Through the sensory testing, I discovered that Jim’s right leg had a much lower sensitivity to vibration, heat and cold. This was most pronounced around his right knee and right ankle. The maps of these areas, therefore, were not being properly updated as there were significant sensory mapping data missing. So the first part of my mission to help Jim run without knee pain was to begin updating those brain maps.

To help update the maps and to also start to improve Jim’s right sided reflexive stability, we spent a couple of sessions where we combined cold sensory input around his right leg with loaded coordination and accuracy drills. This involved exercises such as accuracy shoulder circles, banded punch outs using my reaction lights, and mobilising the nerves around his right side pelvis and right leg.

As we started to make changes, Jim started to feel better about his running and was doing a bit more – and he had ran twice the preceding week without the knee brace. We then started to see the impact of not having the required level of skill to stabilise his joints to the degree needed for an increase in his running. Over the past months, Jim had also had left heel pain but this had been secondary to his right knee pain so wasn’t an initial priority. Now, however, it started to feel worse. Jim had changed running shoes which may also have been a factor, but the main challenge was that he still hadn’t developed the necessary stability skill, and clear brain maps, that he needed in order to increase his running. Determined as ever, Jim was due to run a trail half marathon in a couple of days.

Although that race went well, it was clear that Jim’s left heel pain was now the priority. We shifted focus slightly to deal with that while Jim was still doing the brain mapping exercises for his knee. After a few weeks of doing the exercises, Jim’s heel pain had improved and we put our focus back onto his right knee.

We spent some more time clearing up Jim’s brain maps with a variety of exercises designed specifically to challenge his brain and nervous system to clear the maps up.

The Big Breakthrough

Jim could do a few runs a week now without the brace, and even went for a period of a couple of weeks where he didn’t wear it at all. However, he had become somewhat reliant on it from a comfort perspective. Jim had used his knee brace for so long that his entire belief system about his knee pain was firmly attached to his use of the knee: with the brace, he had no pain and felt fully confident in running up 13 miles. Without the brace he could run without pain, but was always on edge about the possibility of impending tissue damage because he didn’t have the knee brace supporting him.

So now I had the added challenge of changing Jim’s belief system so we could reduce his anxiety around running without a knee brace. As part of this process, we also looked together in some detail at what the knee brace was actually doing for him.

The first thing I did was to demonstrate that his knee brace wasn’t giving any real support to his knee joint at all. It was just a neoprene brace with some plastic hinges built in. Although it was a bit weighty and felt the part, the truth was that Jim could move his knee into every angle very easily and the brace didn’t stop him. If it truly was providing any kind of positional or rigid joint support, he shouldn’t have been able to do that. So if it wasn’t providing significant joint support, what was it doing that was making his running completely pain free when he wore it?

We looked next at whether the heat being generated by the brace was making up for the lack of cold sensory input that Jim had in his knee, and therefore helping to update his map on the fly. There was good logic around this, and if the brace was heating the skin then this would help clear up the map as he was running. This in turn would help his brain activate the muscles better and stabilise the joint: no threat, no pain.

Then Jim told me that at the times when he wasn’t wearing the brace, if his knee hurt he would massage it in the painful area and this often allowed him to continue running for a bit longer. So I decided to get Jim to do some safe exercises that nevertheless irritated his knee, so I could do some testing. Jim started doing single leg squats and sure enough his knee pain came back. So I checked the skin mobility around the relevant area and discovered that it didn’t move very well. Skin stretch and fascial stretch (the deeper layers of tissue) are important sensory inputs that also help to map out your joints, and for Jim the skin stretch sensitivity in that area was poor.

I had Jim squat again but this time I made contact with his skin in the relevant area around his knee at an appropriate firmness and depth, and his knee pain simply vanished. I learned from this experiment that Jim’s knee brace was giving him firm pressure and pushing layers of his skin together which was providing the necessary sensory input to complete the brain map and allow his brain to control and stabilise his knee.

After some more experimentation, I came up with a personalised taping strategy that provided the same pushing together of Jim’s skin and fascial layers. So I managed to replicate the benefits the knee brace was giving him with a simple single piece of kinesiology tape strategically applied, that was both more comfortable and more practical than lugging a hinged knee brace around. Jim found he could complete all of his runs totally free of any knee pain as long as he had used the taping strategy before he ran.

So the big lesson here is that Jim’s lack of sensory input from his skin and deeper layers of tissue in a small area near his right knee, was confusing his brain and stopping the brain maps of his knee from being correctly updated. Combine this with the other sensory deficits and the brain maps were constantly out of date. Because the maps were blurry, his brain couldn’t properly control his knee when he was running. This meant he wasn’t handling the forces correctly which was creating a large threat level for his brain. His brain interpreted this as being unsafe and produced a pain experience to get Jim to stop what he was doing.

Was Jim’s issue fully resolved? No, he still needs to use the tape until such a point where the sensory deficit has been improved. This is going to take time and dedication, and Jim may decide it’s easier just to use a small piece of tape on his knee each time he runs.

So No Strength Work Then?

It’s very common in cases of knee pain for you to be given a load of strength work to improve the activation and strength of the knee and surrounding areas. While this can work in some people at some times, I often find that this doesn’t address the source of the issue. Is strength the ultimate output we want? Yes, but how you go about achieving it is the key.

Jim, like you, already has an abundance of strength in his muscles without doing additional lifting. The goal wasn’t to add more strength. Jim simply wasn’t able to access the existing strength available to him. The goal then, was finding a way for Jim’s nervous system to effectively activate his current strength and help his brain in stabilising his ankle, knee and hips.

Through all of the mapping exercises we did, and then finally with the specialist taping, we were able to do just that. We did use resistance bands at times, but I used these to stimulate stability with light and moving resistance rather than direct lifting work.

As an added benefit, Jim had always had very tight hamstrings – so much so that he couldn’t forward bend towards his toes very far at all. In problem solving his knee and heel pain, we also hugely improved his hamstring flexibility and strength without ever directly working on his hamstrings. Things like that happen a lot when I work at the level of the nervous system.

Main Takeaway

If you’ve had knee pain (or ankle, hamstring, hip pain etc) for more than six to twelve weeks, maybe you need to be looking wider than just some calf raises, clams, squats and lunges. Perhaps your sensory system needs testing to see if there are reasons why your brain won’t allow you to access your current strength. My motto, learned directly from two of the experts I’ve been following for many years, The Gait Guys, is:

Skill, Endurance, Strength

1. Develop the skill first.

2. Add endurance to that skill.

3. Finally, add more strength to that skill if it’s needed.

In Jim’s case, he had to develop a joint stability skill that was currently beyond what he had. We achieved this through mapping exercises, sensory therapy and taping. He is currently adding endurance to this skill through his running and other exercises, and a natural part of this process is accessing more of the strength you already have.

As well as other case studies, look out for an article about kinesiology taping and what you are really trying to achieve – it probably isn’t what you think!