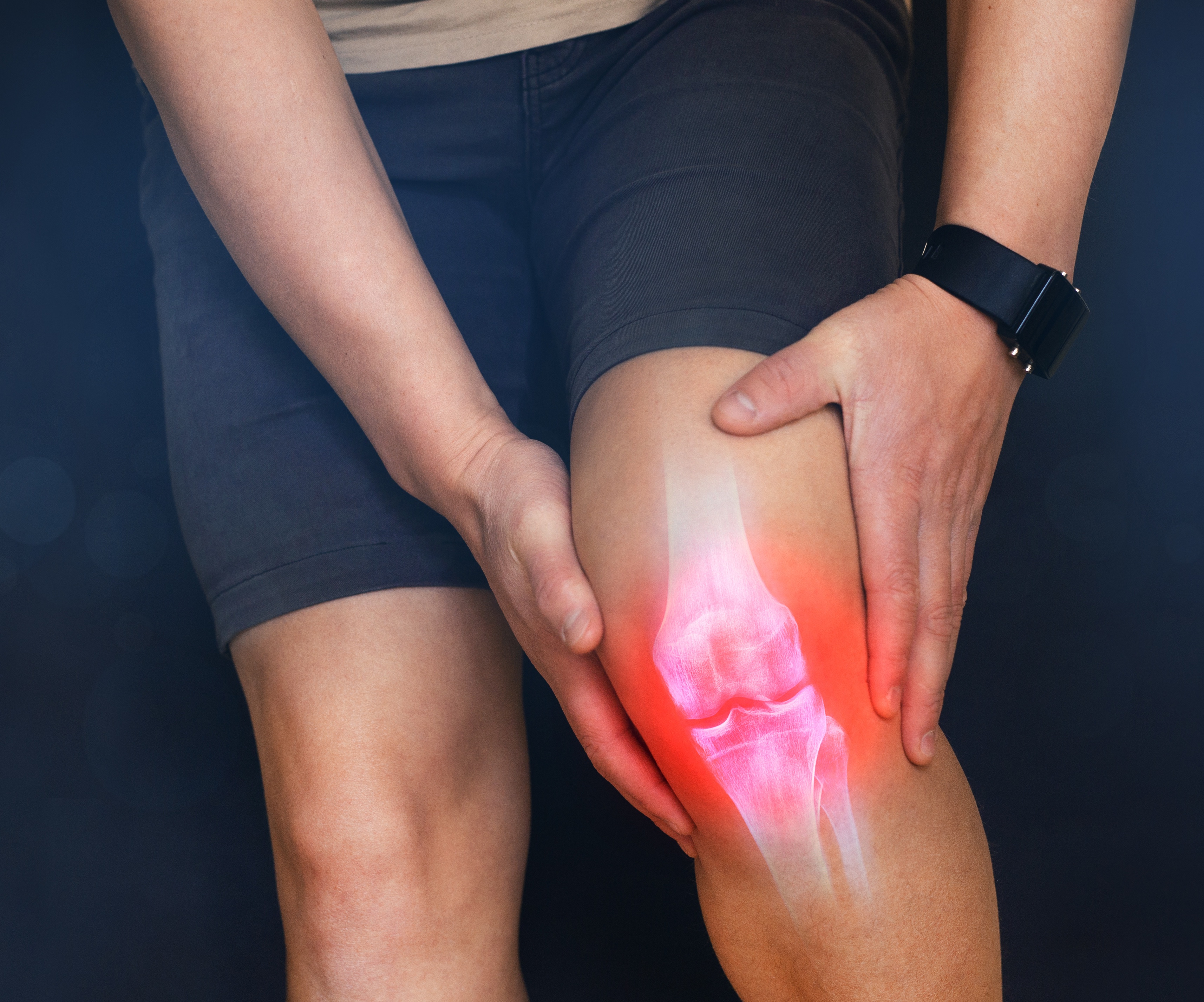

It’s one of the most common injuries that runners complain of – sore knees. It even has its own classification of injury: “Runner’s Knee”. But what exactly is Runner’s Knee and how can you fix it?

Earning The Injury – A Bigger Problem Than Just Knees

Along with the monumental growth of recreational running over the past 10 years or so, there has also been a huge increase in the number of runners getting injured. You may think that’s logical and it does make sense that if the total number of runners increases, so does the total number of injuries. So far so obvious.

But I think the ratio of injuries to runners has got all skewed and the same runners are getting more and more injuries in a shorter and shorter time. In fact, I think that running related injuries in some sectors of recreational running are so common that they are almost worn as a badge of honour! Injuries almost seem to be an inevitable part of being a runner.

This may be common, but it’s NOT NORMAL!

When is it alright to just accept that we get injured? Never! But that’s what seems to be happening and I get disheartened whenever I read about runners getting injured over and over again and often ask myself the question “why?”.

Back To Knees

OK, mini rant over.

So, why does your knee hurt? To answer this question we need to put injuries into two distinct camps:

- Acute injuries that have just happened. For example, you’ve slipped off a curb (or stepped off the promenade which I witnessed an unfortunate gentleman do the other day on the beach) and twisted your knee and ankle. Or, two days ago you banged your knee really hard on the table leg and it’s swollen right up. Or, you’ve unfortunately tripped on a tree root and face planted like a good’un.

I used to split the above type of injuries from the more common running injuries that tend to sneak up on you over time. But in this context it’s more useful to keep them together as ultimately if there are tissue issues, it’s a single point in time where the threshold has been breached and led to those issues – even if it’s been a slow burn to get to that point.

All these are examples of an acute injury that may or may not have resulted in some tissue related issues (strains, tears, breaks etc). In all these cases, your brain thinks you’re pretty stupid and in order to punish you releases huge amounts of pain… No, not really – but your brain does think the behaviour that led to the acute injury was a bit uncalled for and creates a small packet of data called a Neurotag that it can push in front of you next time, just to remind you that doing it again may be a little silly and this can trigger caution – a good thing.

What actually happens at the brain level is that the area that received the physical injury goes on heightened alert and special threat sensors in the tissues send signals to your brain alerting it that there’s either an issue or a possibility of an issue.

If your brain thinks the situation is important enough (based on a lot of past and current data), it will produce an output to get you to change your behaviour. In the case of acute injuries it’s normally quite a bit of pain so you pay attention to not using the injured area until it’s had time to heal.

The threat sensors, called nociceptors, stay at a high sensitivity until such a time that the tissue has recovered enough that you can go back to using it. Essentially, the nociceptors create a buffer zone around the injured area that if you try to access (i.e. move, put weight on, put force through, etc) the brain’s response is to create an experience of pain to remind you to back off.

Under normal circumstances, most injuries will have recovered to a state where the sensitivity of the nociceptors has gone almost back to normal within six weeks. Under certain conditions this can take longer, but rarely more than 12 weeks for most of the common injuries. Of course, there are always exceptions so it’s always a good idea to get things checked out by medically trained bods if you are in any doubt at all.

So, in summary: acute injuries, whether they actually result in tissue issues or not, are injuries that have happened somewhere in the last 6 weeks. They usually cause an increase in sensitivity in your threat receptors (nociceptors) that in turn triggers the creation of a buffer zone. This buffer zone is closely monitored by the nociceptors and they inform the brain if you try to breach it. In response, your brain creates the experience of pain to remind you to reign it in. Usually, but not always, this buffer zone shrinks as the tissues recover and the sensitivity of the nociceptors returns to normal. - “But I’ve had my pain for months!” I hear you cry. I know, I know, we’re coming to that now. The second category or injury was what used to be called chronic injury. This is the pain and apparent injuries that just go on and on and on. So what’s happening here?

At this point it’s really useful to separate out injuries from pain. You may have gathered from the acute injuries section that injuries and pain aren’t necessarily linked. “Whoa!!! Wait, what???!”. That’s right, injuries and pain don’t need to be bed buddies – you can have one without the other. I know, mind-blowing isn’t it. But you actually already knew that. Here are some examples:- Military personnel injured on a battlefield that don’t feel any pain until they are in a hospital.

- The guy in Australia who walked down the high street with an axe in his head, even stopping to buy a sandwich from a convenience store on his way to the hospital – didn’t feel a thing.

- That cut you just noticed on your finger and now hurts because you’ve seen the blood.

- Phantom limb pain where the pain is somewhere in the limb that’s no longer there.

- And countless other examples, both major and minor.

So what we are really talking about in this section is chronic pain rather than injury, now often referred to as long-term pain. This will make more sense in a minute, I promise.

Remember in the acute injury section I mentioned that usually, the buffer zone reduces within six weeks? Well, sometimes the system just doesn’t work very well for one reason or another. This means the buffer zone stays put and the sensitivity stays high. In fact, the sensitivity can even increase and this can become a real problem. The key thing here is that while the buffer zone stays where it is and the nociceptive sensitivity stays high, the actual tissues themselves are recovering exactly as they should. This results in…dun, dun, dun…..

Pain without injury.

So it is completely feasible, and actually very, very common, that if you’ve had pain for more than at least six weeks, your are moving into a chronic pain state where the injury (if there even was one at all – don’t worry, that’s for a different day) is recovering well but the system isn’t resetting. This results in your brain being tricked into thinking it needs to keep giving you the experience of pain so you avoid using the now non-injured area.

Does that mean you should just push through the pain if you’ve had it longer than six weeks? NO! STOP! DON’T EVER DO THAT!

Pain MUST Be Paid Attention To

Even if you’ve had the same pain for many weeks, months or years, you should always pay attention to it. Pain is an output from your brain to let you know something isn’t right and you need to take action. Even if your nociceptive sensitivity and buffer system hasn’t reset properly, you still need to pay attention to the pain experience.

There are many things that could be triggering the threat levels in your nociceptors and stopping the system from resetting. Often, I find this is connected with a poor sensory or motor map of a joint at one side (or both sides) of the painful area.

If, as part of the original injury (even if it was years ago) some of your sensory ability may have been affected, the joint maps may be incomplete. Your brain uses this sensory input to help determine where a joint is, and how to activate and control the muscles and connective tissue in supporting the functioning of that joint.

This can also impact your ability to stabilise your joints when running, and you can probably guess that this itself presents a huge threat to the brain. In turn, your brain produces a pain experience to get you to stop doing the actions leading to the threat, and you get in a cycle of threat-pain-threat-pain etc.

This can be hard to break, particularly with traditional strength-type training and rehab as they almost completely miss the mark of how your system needs to be treated for those sensory systems to be up-regulated and stimulated.

Paying attention to your pain experience can give many clues as to the underlying cause(s) and is often not directly related to the painful area at all. Ignoring your pain experience can lead to unhelpful compensations that can then lead to other acute injuries, whether of the immediate kind or the slow burn kind.

So, Why Does My Knee Hurt?

Hopefully, this article has helped you to understand that injury and pain aren’t necessarily linked, and you can have one without the other. You will also appreciate that sometimes your system doesn’t reset correctly following an injury (or perceived injury), and this can lead to long-term pain because something is still causing a threat to your brain and until you deal with that something, it can be a very long road back. This is often the reason why you may get recurring pain in the same or a similar area.

So the real answer to “Why Does My Knee Hurt? AKA Runner’s Knee” is:

It Depends…

Over the next few weeks I’m going to write up some of the case studies of runners that I’ve worked with where we’ve approached their knee pain, as well as other “injuries”, at the level of the nervous system rather than just always going for “strengthen, strengthen, strengthen” in the traditional way.

This means that I’ve assessed how and why their nociceptive system isn’t resetting as it should, and we’ve designed specific drills and exercises, as well as things like specific taping strategies, to make incredible progress – even when they have already seen everyone else and done everything else.

I hope you’ve found this article interesting and it’s raised some questions about how you currently approach your running injuries and pain. As for the answers… you’ll need to open your mind and stay tuned for more articles.