Hotting up

Hydration! With average temperatures starting to rise as we progress through spring and into summer, we are blessed with a few sunny and hot days (for us Brits anyway!). And while the sunshine brings us smiles and joy, it also brings with it a dilemma for us runners:

How do I hydrate? What do I drink and how much?

As you look out the window, the sky a magnificent blue, you are desperate to get out for your run. But wait… your mind starts racing and a mild panic takes hold.

“Have I drunk enough? Is plain water okay? Do I need to take water with me? I read something about electrolytes, I better grab a bag of them (even though I don’t really know what they are)…. Help, I just want to run and not die, why is it so hard?!”

There is so much confusion around hydration, dehydration, heat stroke, hyponatremia (what?) and self-drowning (yep). Now add in euhydrated, hypohydrated, hyper-hydrated, hypotonic, hypertonic, isotonic… arghhhhhhhhhhhhh – can I go out and run yet?

Keeping hydrated is a serious business and yes, behind the scenes there is a lot going on. But once you have a basic understanding and a feel for how your body reacts under different conditions, it can be pretty simple. Don’t allow yourself to get drawn into the marketing hype.

Let’s start right at the beginning….

Fluid intake is episodic (every now and again). Fluid loss is continuous (all the time, no matter the weather, climate, temperature, etc)1.

Under normal conditions, our body regulates our water intake and output. While it fluctuates throughout the course of a normal day, it usually gets back to the same point over a 24-hour cycle2.

Our little challenge is to deal with potentially larger fluctuations when we are going out for a run. More-so over longer distances, higher intensity, and higher temperatures and greater humidity. Add in to this the fact that we don’t want to be stopping for a pee every 10 minutes ( I would have got a PB but….)!

What is hydration and dehydration?

There are several definitions about, but all are very similar:

Hydration is…

the process of causing something to absorb water 3.

The process of combining a substance chemically with water molecules 4.

the process of making your body absorb water or other liquid 5.

Dehydration is…

The process of losing or removing water or moisture 3.

Dehydration is a condition that results when the body loses more water than it takes in 6.

A condition caused by the excessive loss of water from the body, which causes a rise in blood sodium levels 3.

We classify dehydration into one of three categories:

- Mild dehydration

- Moderate dehydration

- Severe dehydration

Most of us have a pretty good idea about what hydration and dehydration is, and we know we need to keep hydrated. But what exactly does keep hydrated mean?

First, let’s look at what the continuous loss of water from the body – why does it happen? Well, we lose water by…

Sweating, peeing, pooping, tears, saliva (spitting) and breathing.

These are normal everyday events for most of us. We also lose water through less frequent events (depending on how often you are adventurous with your nutrition perhaps…)…

Diarrhoea, vomiting, fever, excessive sweating, excessing peeing (for example diabetes and some medication such as water pills).

But, we also take water in from a variety of sources:

Direct water intake, as part of other fluids/drinks and through food.

So this now brings us to the term euhydration. This is the state at which our body is in hydration/dehydration balance:

Normal state of body water content; absence of absolute or relative hydration or dehydration 7.

And this is the state that we should be starting all our running in. It’s what I call “properly hydrated”. If we start a run properly hydrated, and depending on how we get to properly hydrated (more on that in a minute), we are much better able to determine our fluid needs for that run.

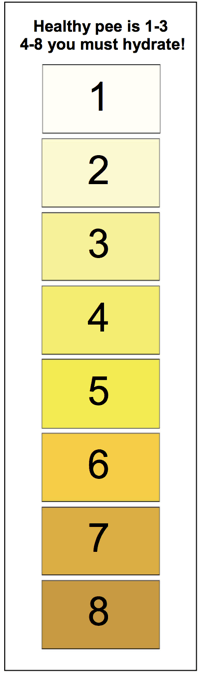

The most simple indicator that we can use to determine whether we are properly hydrated is urine colour:

While feelings of thirst, dry lips and headaches can also provide clues, these symptoms can be from other things as well so urine is pretty reliable. Be warned though, some foods and supplements can cause your pee to change colour – too much vitamin C can make it go bright yellow, for example.

The NHS recommend between 1.6 and 2 litres of water per day, but that includes the fluids you get through food intake (approximately 20%). But we need to adjust this for the environment, our exercise intensity, and our individuality. We all sweat at different rates, so we lose water at different rates.

But it’s not only water that we lose. This brings us to electrolytes. Electrolytes are substances that create an electricity-conducting solution when mixed with water. Common examples of electrolytes are Sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, magnesium, and phosphate. They are vital in the chemistry of our bodies, and are usually replaced through normal food intake.

However, when we sweat heavily we lose more than we can replace. This is also the case with vomiting and diarrhoea. This loss is then made even worse when we try to replace the lost fluid by drinking a lot of plain water. This dilutes the fluid in our bodies further, and effectively ‘washes’ the sodium (salt) out. This is bad news and can result in hyponatremia, a condition where the sodium level in the blood is too low. Our cells swell and this can cause a host of health issues, being fatal in extreme cases.

Overhydration, where we are taking on too much plain water, is a significant cause of hyponatremia. We see this condition in long running events such as the marathon. Some runners take water at every aid station and end up severely overhydrated – sometimes with fatal outcomes.

Getting the balance right

So now we are properly hydrated before we start, we need to determine whether we need to drink fluid on our run or whether we’ll be okay until we finish. Sometimes this can be an educated guess (for example a cool 5k or 10k, or a hot 20 miler), and sometimes we need to think a bit more about it. A lot comes down to experimenting and personal feedback. There are online sweat tests that can be taken to help determine your sodium loss per hour. This can help you decide what type of fluids you are going to need.

In my own experience, drinking up to 500ml of either water (if going for a short, cool run) or 500ml electrolyte solution (for everything else) in the hour before running gets me to my starting point of properly hydrated. If it is going to be an intense, long or particularly hot session, I’ll drink more than 500ml of the electrolytes solution or make that solution stronger. A lot will depend on what I have drunk up to that point of the day.

Also worth considering is that if you eat a low carbohydrate, low refined food, or low sodium diet, you made need a slightly higher level of sodium on certain days (all these diet types are generally low salt). However, this will also depend on how long you have been “low salt” and whether your body has fully adjusted to that or not.

A study published in the Journal of Clinical Nutrition1 in 2015, looked at the water retention rates of a range of drinks. They did this to see if certain drinks could help us retain the water in our fluid intake for longer, therefore being quite practical in situations where we can’t always take on frequent amounts of fluid – and where we don’t really want to be peeing all the time. Sounds ideal for runners.

All the drinks were measured against the baseline of plain water, and the drinks included: plain water, sparkling water, tea, coffee, cola, diet cola, a specific electrolyte solution (oral rehydration solution), a sports drink, orange juice, lager, full-fat milk, skimmed milk and a few others.

Conclusion

They concluded that over after a four hour period, the amount of urine from the specific electrolyte solution (oral rehydration solution) and the full-fat milk was less than that of pure water. This means they had better water retention properties than plain water. All the other drinks were the same as plain water.

Even over a two hour period, only the electrolyte solution, full-fat milk and skimmed milk were better than water at retaining the water.

So what does that tell us? While no research can tell us how your body will react, it does seem clear that drinking a solution of water and electrolytes is better than water alone when we want to stay hydrated over a longer run. If we are heavy sweaters or otherwise have low salt diets, we can probably come to the same conclusion – drink water with electrolytes, but not the commercial sports drinks as they don’t seem to help in this situation, and most still contain quite a lot of sugar. There are however, quite a few specific hydration or electrolyte products available from companies such as High5, SiS, SOS (20% discount code: CHRIS20), OSMO, elete, etc.

So which electrolyte product should I use? We’ll get onto that in the next post 😉

The key here though, is to experiment with different strategies to find the one that works for you. I prefer to be properly hydrated or even pre-hydrated before I run. Pre-hydration, as far as I’m concerned, is topping up both my water and electrolyte levels before I run – especially before long, hot or intense sessions. That way I know my starting point is good. I also drink an electrolyte solution after I run.

By pre-hydrating and through experimenting, I have also trained myself to run 15 miles or so on a cool day, without needing to take fluids with me. On a hotter day, I always take an electrolyte solution if my run is going to be over 10k. But, I don’t carry a water bottle in my hand. Why?….

One last thought…

Carrying things in hands while running changes your running mechanics. Carrying a water bottle while running will alter the way you run, and over time this could lead us down all kinds of avenues we would rather not go (injury mainly).

Instead of carrying the bottles in your hands, use a race vest or hydration vest. I prefer a race vest and then put a small bottle (or two) in the carrying pouches. I find that with hydration vests (CamelBak, etc.), the water gets warm from being against your back and that’s just yuk!

So there you have it:

- Use your pee as an hydration guide

- Always try and be euhydrated (properly hydrated) throughout the course of a day, adjusting for your environment. Add electrolytes (even at work) if necessary

- Experiment with plain water and also with electrolyte solutions during and after your run

- Prehydrate (not overhydrate!) and train yourself progressively to run further/harder without needing to carry fluids. The keys are train and progressive.

- Be sensible and listen to your body, and stay safe. Too little or too much is never a good thing

As an ambassador for SOS Hydration, I am able to offer everyone a 20% discount. I love their product, which is why I was keen to become an ambassador for them. It is easy on the stomach and certified organic. You can buy SOS from:

SOS website and use the discount code: CHRIS20 for your 20% off

(https://sos.refersion.com/c/8a7923)

REFERENCES

-

- Ronald J Maughan, Phillip Watson, Philip AA Cordery, Neil P Walsh, Samuel J Oliver, Alberto Dolci, Nidia Rodriguez-Sanchez, Stuart DR Galloway. A randomized trial to assess the potential of different beverages to affect hydration status: development of a beverage hydration index

- Leiper JB, Seonaid Primrose C, Primrose WR, Phillimore J, Maughan RJ. A comparison of water turnover in older people in community and institutional settings. J Nutr Health Aging 2005;9:189–93.

- Dictionary.com

- https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/hydration

- https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/hydration

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dehydration/

- www.medilexicon.com/dictionary/30690